Bioserenity : le t-shirt connecté contre l’épilepsie

30/08/2014How technology can help tackle the rising cost of healthcare in Asia Pacific

30/08/2014How An App Helped Me (And 20,000 Other Women) Get Pregnant

Last summer I sat in the bathroom of an Irish pub, trying desperately to solve a math equation. I had abandoned my friends at the bar, where I’d been pretending to drink an IPA, to tend to this pressing arithmetic in private. If I solved correctly for ‘x,’ the answer would provide me with some crucial information—whether or not my pregnancy was going well.

Earlier, a key number in this formula had been left on my voicemail by a nurse at my doctor’s office: The level of my human chorionic gonadotropin (or hCG), a hormone the body starts making a few days after conception. The hCG number was supposed to be doubling roughly every 72 hours since then, according to a website I’d somehow Googled myself to—after I’d looked up what the heck this hCG thing was.

But I was missing one bit of information. « What we need to know, » the nurse had said, « is when you got pregnant. » Although I had a few rough estimates, based on, you know, having sex, I really had no idea. With my doctor’s office now closed, it was up to me to master the sperm-egg algebra in this sticky, wood-paneled stall. I plugged in a few different potential dates, feeling for the first time in my life like my body was a foreign mass I happened to wear around me like a vintage sundress.

As I crunched the data, I started to see that even with the most generous calculations, my hCG wasn’t behaving the way it was supposed to. There, with a faux-vintage Guinness mirror over my head, I realized that my pregnancy probably wasn’t either.

I’d always known I wanted to have a family, yet I never experienced those maternal urges that everyone swore I’d start to feel as my biological clock ticked past 30. When my husband and I got married, that seemed as good a reason as any to get started. But I was still in no rush. During the winter I turned 35, I stopped taking my birth control pills. By summer, I was pregnant.

Or was I? The restroom math I hoped I had calculated incorrectly was confirmed a few weeks later at the doctor’s office, as she peered inside my uterus with an ultrasound wand. Even with my shameful ambiguity factored in around when I’d actually conceived, she should have seen a viable embryo, a tiny heartbeat flashing like an LED bike light. Instead, there was only a hollow ring. She shook her head. « No, I’m sorry. »

She left me in the room to change, the image of my empty womb still on the screen. I slowly reached over for my clothes, completely blindsided. The pregnancy that I’d casually and somewhat ambivalently stumbled into had been snatched away from me by a grainy image on a black-and-white monitor.

And suddenly, all I wanted in the world was to be pregnant again.

Since nobody ever talks about miscarriages, I can’t really say that there are a few things I wish someone had told me about miscarriages. But here are three things I figured out about miscarriages after I had one. I’ll call them two truths and a lie.

First truth: Miscarriages are far more common than you might think. If you asked three women of childbearing age that you know, chances are at least one will have lost a pregnancy. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists believes that up to one in five pregnancies will end in miscarriage. Many miscarriages are early, though, so sometimes women don’t know they actually had one, attributing it to a late period.

Second truth: Most women will get pregnant again without any problems—miscarriage is not always a sign that something’s wrong with you. Many miscarriages are the result of a random genetic abnormality that’s determined at conception. Or as I like to think about it, a « bad egg » (or sperm!). As your body ages, you’ll statistically have more bad eggs. That’s why as you get older, your chance of miscarriage goes up.

And here’s the lie: The miscarriage itself isn’t the worst part. It’s the days or weeks or months or years after it’s all over, as you impatiently wait for the hormones to slowly evacuate your body, searching « miscarriage » on your phone in bed with the brightness level cranked way down so you don’t wake up your husband, holding your hands over your abdomen as you sob quietly in the dark, wondering if you’ll ever get pregnant again.

It was during one of those 2:00 a.m. Googling sessions that I stumbled upon a story about Glow, an app that was helping women concieve. I’d seen plenty of those those cycle-monitoring sites: cursive logos, a URL with « fertility » or « ova » inevitably embedded in it, lots and lots of pink. They worked by helping you track certain subtle hints associated with ovulation, like a basal body temperature increase and a change in your cervical mucus. I thought back to the first time I tried to get pregnant, when I jotted down fragments of data every few days (okay, whenever I remembered) on the paper chart that came with my Target thermometer. This seemed like even more work I wouldn’t do.

Expand

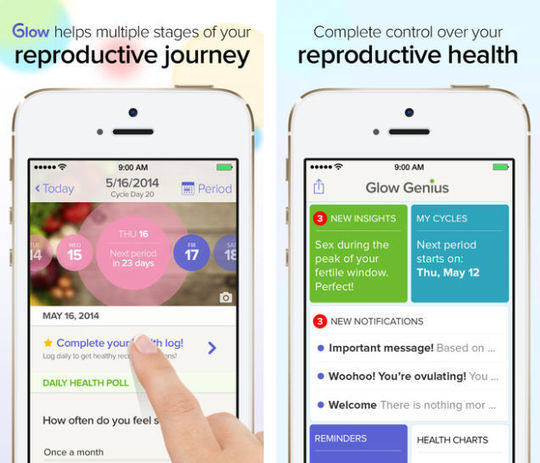

Glow was designed to stand apart from its wide range of competitors with clean graphics and colors other than pink (thank goodness)

But there was something about this one that made me keep clicking. First, it was good-looking: It was almost like it was designed to match the new look of iOS 7. It also talked to me like an adult. Instead of cheesy euphemisms and abbreviations for periods and intercourse, the information was presented in normal, grown-up language. But here was the real clincher for me: The app was blue and purple, not pink.

Plus, it had something called Glow First, a kind of crowdfunding savings plan for couples having trouble conceiving. We could choose to pay $50 per month which would go into a fertility fund. After 10 months, most of the couples would get pregnant, statistically, and those who didn’t would get to split the rest of the money for fertility treatments.

I downloaded Glow.

In over two decades of seeing reproductive health practitioners, not a single doctor had ever suggested that I track my cycle. When I had started to entertain the idea of getting pregnant, I asked one of my doctors for tips on what I should do, and she looked at me rather oddly and offered this sage advice: « Just have sex. »

But as I would come to find, it’s not actually that easy. The fertility window is already pretty narrow, and as you get older you’re honestly only looking at a day or two when you can actually get pregnant. When you’re 35, you don’t have time to be casual about it. I realized that I had spent far too much of my life clueless about the happenings in my pelvic region. I wanted all the information laid out cleanly for me. Very quickly, and with lovely graphics that didn’t offend my discerning taste, Glow managed to illustrate everything I didn’t know.

Expand

The daily log tracks fertility cues as well as health information. The app actually made gathering information about cervical mucus (CM) pretty fun (well, as fun as it could be)

Using the app was enjoyable. I’d tap in my temperature and other fertility cues during my morning Instagram-feed viewing. Later, I’d fill in basic health information about my day—exercise, alcohol consumption, energy—while riding the bus. (Now the app syncs with fitness trackers to import all that data as well.) When I didn’t log information, the app would ping me. But I didn’t need the reminders very often. I became diligent about tracking. My husband was able to download the app, too, and have access to all my information. Dare I say, it was almost fun.

Right away I started to see patterns which surprised me. It turns out that even though I have a pretty average 29-day cycle, I ovulate really late, usually on day 17 or 18. Which means if I was going by the « typical » day 14 ovulation most women experience, I would have been missing my fertile window completely. In fact, this is one of the biggest insights Glow has gleaned from their users, says Jennifer Tye, Glow’s head of marketing and partnerships: 50 percent of women are incorrectly estimating their cycle by up to four days.

I was intrigued why Glow would know something so specific about its users until I learned more about the company’s roots: Glow was actually started by PayPal founder and Yelp chairman Max Levchin, who had identified fertility issues as a problem in need of a tech solution. « We’re a data company at heart, but we’re taking these capabilities from data science and machine learning and applying them to the very real world issue of reproductive health, » says Tye.

Expand

An infographic prepared by Glow showing where 20,000 of their users have conceived and how up to half of their users were incorrectly estimating their cycle length

The data-driven perspective also informs Glow’s educational focus and the way it talks to its users. « Educating women before conception is something we feel very passionately about, and that includes both physical and mental health, » says Tye. « We’re able to to flag potential risks or concerns and we approach it with very personal perspective. If you start to look things up on the internet you can end up reading a lot of scary stuff, so the goal is to give you insights that are specific to what’s going on with you. » The personalized information is what helped the app immediately feel relevant and useful to me: I got daily links to studies about fertility over 35 or getting pregnant after a loss.

Some women do need medical intervention to get pregnant. But Glow can help diagnose some of those problems, says Tye. Certain fertility issues, like polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), have symptoms like extra-long cycles which Glow’s algorithm will isolate. A woman experiencing this might get a message telling her to ask her doctor about PCOS. Glow can then train the app to ask better questions related to symptoms that might be red flags.

The detailed information Glow is collecting can reveal very nuanced insights, like how often couples in their 20s are having sex during their fertile window or how long it takes for the average 35-year-old woman to get pregnant. In fact, Glow is presenting details culled from their first year of data collection at the American Society of Reproductive Medicine later this year. While they don’t release figures for how many women have downloaded their app, Glow does have one number they’re proud to promote: In less than a year, Tye says Glow has helped 20,000 women get pregnant. There’s even a name for these successes: « Glow babies. »

Source: gizmodo.com